THE ROAD TO HEALTH SERIES: Breathing and Physical Activity – part II

It’s time to go back to the subject on breathing and physical activity (you can read the first part HERE). In the second part of the post from the series “The Road to Health. Do you know that…?” by Martin Petrus you will learn about a variety of breathing techniques that can improve efficiency and concentration, as well as support the process of effective regeneration. A good dose of useful knowledge awaits so let’s have a look ?

FITNESS

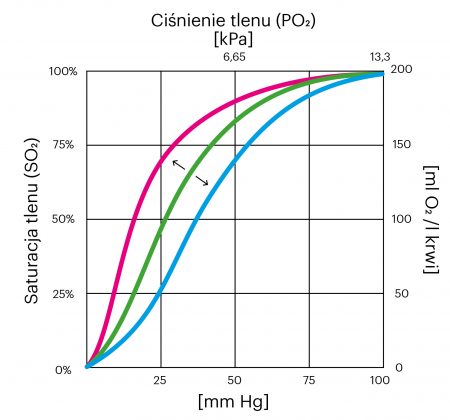

One of the steps of improving efficiency will be training the respiratory muscles. Another very important point will be to increase the tolerance to carbon dioxide. According to the Bohr effect, we need enough CO2 in the blood for oxygen molecules to be released from hemoglobin. Simply put: the better your CO2 tolerance, the better the release of oxygen from your blood.

How do you test your carbon dioxide tolerance?

The first test is Control Pause (CP) proposed by Dr. Buteyko, also known as the BOLT test (Body Oxygen Level Test). We exhale slightly, leaving approximately 40% of the air in our lungs, and hold our breath until the first moment we notice a shortened diaphragm or throat. We measure time to the first signals that our body gives us – this is CP. It is important to end the test after the first signals from the body, as we are able to extend the breath hold time with our willpower (and we need the objective first physiological response).

The norm for healthy people is 20 seconds. The result below may indicate a respiratory disorder such as asthma or shortness of breath. A CP of more than 35 seconds indicates good physical fitness and an efficient respiratory system, so for people who practice sports this is the result that we should strive for. I have met people with a CP of over 45 seconds a few times. This group includes people who practice martial arts or freediving and have actually spent a lot of time working with their breathing. However, I also met with world-class athletes – even Olympic ones – with a CP of 15-20s. This result proves that, despite the above-average efficiency, the tolerance to carbon dioxide is still very low. Amazing achievements are possible, but they are associated with a very high burden on the body. In the case of these people, we can still improve a lot by increasing their tolerance to CO2.

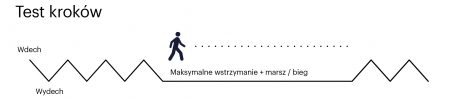

The CP test can also be performed in an active way – while we walk and count the steps. The same rule applies here: exhale gently, hold the air and count the maximum number of steps you can take. In this case, we do not pay attention to the shortened diaphragm, but hold the air as much as possible.

The third option is the exhalation test proposed by Brian MacKenzie. We breathe through our nose all the time. We take three light breaths, then a very large breath, start the timer and start exhaling. We try to keep one long, uninterrupted exhalation. If we stop even for a moment, we stop the test.

- < 20s – poor

- 20-40 – average

- 40-60 – intermediate

- 60-80 – advanced

- > 80s – elite

We can choose one type of test that suits us best. If we do two or three tests, then the obtained result will of course be more precise. In all trials it is important to remember that whatever you do before the test will have an effect on the result. Even a few deep breaths will empty our body of CO2, which will radically change the result. The most important thing for us is how breathing exercises influence our progress, so ideally we should do this test every day.

How can we increase our tolerance to carbon dioxide?

If nasal breathing is not natural for us, it can have a significant impact on overall blood CO2 levels. Breathe lightly can be a good exercise for beginners in this case. I’ll describe it later on.

For the more advanced, I recommend practices from the world of freediving, namely the Wonka Tables. We take one big breath in and hold our breath. When the first diaphragm contractions appear, start the timer and count down 15 seconds. After this time, we breathe out once and inhale once, and then repeat the sequence. When contractions in the diaphragm appear again, we start the stopwatch and count down 15 seconds, then repeat the entire sequence again. If keeping these 15s is easy for us, we can extend the time. The advantage of this exercise over standard CO2 tables is that by taking just one breath between the sets, you don’t get rid of too much CO2, because it’s all about accumulation.

Actually, we are still learning about the whole spectrum of the influence of carbon dioxide on our body. We already know e.g. about the Correlation of CO2 tolerance and the frequency of injuries – greater tolerance goes hand in hand with fewer injuries. The effect of carbon dioxide on the sense of fear has also been studied. The amygdala, which is largely responsible for the feeling of fear, is also an acid receptor. So the question is whether we are able to influence how we feel fear by working with carbon dioxide. The effect of CO2 on accelerating the healing of damaged muscle tissues is also very interesting. Because research on breathing is still ongoing – we are constantly learning about the benefits we get from increasing our tolerance to this gas.

Altitude training

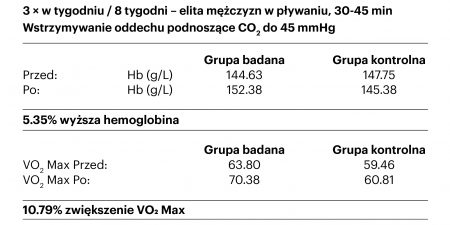

One of the best exercises that can positively affect our efficiency is the simulation of altitude training. When we are in an environment where the oxygen level is lowered, our body is forced to adapt. The concentration of hemoglobin increases (the number of red blood cells increases), thanks to which we improve our ability to transport oxygen. In-depth research on altitude training began after the Mexico Olympics in 1968, where it was noticed how adaptation to low oxygen influences athletic performance. Currently, the most effective method is LHTL (Live High / Train Low) – thanks to it, we can all have adaptive benefits from staying at high altitudes, while our training is not limited by low oxygen levels. Given the cost and logistical challenges of altitude training, athletes often choose hypoxia generators that they can even use at home.

IHT Training

An alternative will also be breath holding training – IHT (Intermittent Hypoxic Training), also popularly known as altitude training simulation. Since 2000, Dr. Xavier Woorons has been writing about the Exhale-Hold technique, which is an excellent example of IHT. A similar procedure was also proposed by Patrick McKeown in the Oxygen Advantage methods. Thanks to this type of exercise, not only are we able to temporarily lower the level of oxygen, but also increase the level of carbon dioxide. At this point, we have a double stress stimulus forcing the body to adapt.

The technique is really easy: we breathe out slightly, leaving about 40% of the air in the lungs and hold our breath. At this point, we can either statically hold our breath or add activity such as walking, running, squats, or any other movement. Thanks to this, we burn oxygen faster and additionally our muscles produce more carbon dioxide. To check whether our training is effective, we can use a pulse oximeter.

After holding your breath, your oxygen level should begin to decline slightly. If we are able to lower SpO2 to the range of 80-90%, it means that our body has received the appropriate stimulating dose. During breathing exercises, the time we are hypoxic is relatively short, while even 15 series of breath-holds a day are enough to stimulate adaptation.

In studies conducted on a group of elite swimmers who trained 3 times a week for 8 weeks, it turned out that: 5.35% higher hemoglobin equals 10.79% increase in VO2 Max.

The breath-holding technique not only triggers processes such as the release of blood rich in red blood cells or the activation of erythropetin (EPO), but it is also a very powerful stimulus for our mind. The discomfort we experience while holding our breath for a long time is enormous. Thanks to this, we can get used to this feeling, which is useful during competitions or intense training.

REGENERATION

It is a crucial part of our activity. Our autonomic nervous system regulates our body functions in such a way that we are ready to act at the right moments, but rest afterwards. In the traditional model of the nervous system, this will mean two modes: sympathetic, responsible for action, mobilization, but also the stress response popularly known as “run or fight”, and the parasympathetic mode responsible for relaxation, rest and regeneration. There is also a freeze mode in Stephen W. Porges’s Polyvagal Theory. If the stress level increases so that flight or fight is impossible, then the body goes into a state of dissociation and withdrawal. Fortunately, freeze mode doesn’t happen very often, but also spending too much time in the sympathetic mode isn’t good for us. When a gazelle runs away from a cheetah fighting for its life, it undoubtedly experiences enormous stress, but after a successful escape it is able to quickly return to picking grass. It does not need several years of therapy to deal with the trauma. This very useful natural mechanism, which works perfectly in animals, is often disrupted in humans. When we are energized and ready all the time, we do not give ourselves enough time to regenerate. Simple breathing exercises can help us consciously enter the parasympathetic mode so that our regeneration begins immediately after training.

Our body likes rhythms because practically the whole world moves in cycles. Our body is heartbeat, breaths and pressure changes. There is a reason why dancing or rocking relaxes us. This is why in many rituals of ancient cultures the rhythm of the drums was used to bring the body into a proper state. Likewise, traditional breathing practices have very often used rhythmic breathing.

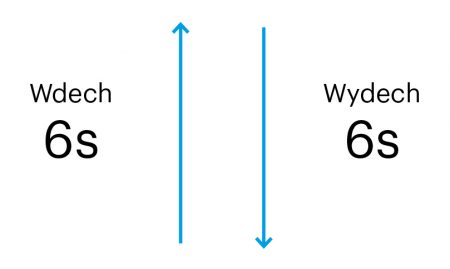

Rhythmic breathing

Let’s start with the right position. Depending on our needs, we can practice while sitting on a chair, on the floor or even lying on our back. The important thing is to keep the body in a straight and stable position so that the diaphragm movements are not restricted. You can also lean your legs against the wall after intense training. We start to breathe rhythmically through our nose, counting up to four (that’s about four seconds) – inhale at four and exhale at four. When, after a minute or two, we find our optimal rhythm in which we notice that our breathing is light and effortless, we can slow down our breathing, e.g. inhale at 6 and exhale at 6. Then 8/8, 10/10, 20/20, etc. As soon as we feel a strong sense of lack of air or suffocation, we return to a lighter cadence or completely return to normal breathing for a while.

Even such simple breathing rhythms can have many benefits for us. The HeartMath Institute, located in the United States, studies how the heart works. It turns out that even a simple rhythm like 6/6 or 8/8 can introduce us to the so-called State of Coherence. After a few minutes of this type of breathing, our rhythms of breathing, heartbeat and blood pressure become synchronized. An exceptional state of equilibrium occurs, which is also manifested by an increase in the HRV factor (Heart Rate Variability), which indicates an increased activation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

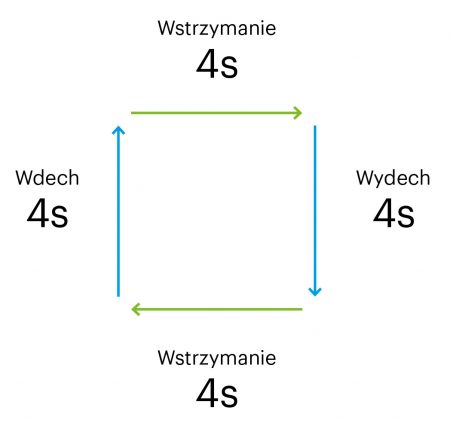

Another rhythm that can be of great help to us is Square Breathing where we have equal durations to inhale, hold, exhale and hold. For example: inhale 4, hold 4, exhale 4 hold 4. Likewise, in this case we can slow down the whole sequence to 6/6/6/6, 8/8/8/8, 10/10/10/10 etc.

This type was adopted by Navy Seals commandos as “Box Breathing” or “Tactical Breathing” to help manage stress at crucial moments.

When we take into account that breathing in is usually more energizing and the exhalation is more relaxing, we can adjust the sequence to our needs. Inhale, hold, exhale will therefore be more energizing than inhale, exhale, hold.

The currently discussed, popular and important topic is sleep optimization. If we work with this most important phase of regeneration, we will not only have a positive impact on building our form, but we can also save a lot of time. The point is not to sleep long, but to get the optimum sleep pattern. Sometimes falling asleep is not easy and introducing even five minutes of rhythmic breathing while lying in bed can make a huge difference, relax us, and put us into a state of rest.

THE MIND

Both in sport and in everyday life, concentration is one of the most desirable qualities. Unfortunately, our ability to focus our mind has become worse. In 2013, Microsoft published a study showing that the average focus time is 8 seconds. The flood of technologies that capture our attention has certainly contributed to the decline in concentration: in 2000, the average focus time was only 12 seconds, so not much more.

Concentration is also the most important component of the so-called Flow States. If we’ve ever caught ourselves losing track of time while practicing sports, and our body behaves perfectly well, reflexes are perfect, mental focus is above average, we’ve just experienced the flow state. This type of flow can happen while playing tennis, jazz improvisation, programming or even peeling potatoes. Many experts believe that thanks to them, we can not only achieve above-average productivity, but also have a positive effect on our body by activating natural self-healing processes.

Practices of improving concentration have been known for a long time. Focusing on one object, words, or feelings in the body are just a few examples of how we can work with our mind. One of the best known and available techniques is breath observation. When our mind is so distracted that observation is too difficult, we can try to slightly modify our breath to increase our alertness.

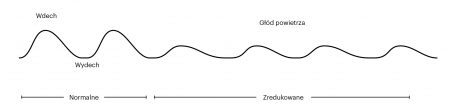

The Breathe lightly exercise used in the Buteyko method is ideal for this. Originally, it was supposed to adapt our body to greater tolerance to carbon dioxide, but it works great as a method of improving focus.

In this exercise, we try to breathe less air than normal for a longer period of time, without increasing the pace of breathing. Thanks to this, we exhale less carbon dioxide, which causes its accumulation in the blood. You can feel it immediately with an increased sense of air hunger. Of course, our blood oxygen level will not decrease dramatically and this feeling is only related to the increased amount of carbon dioxide. What we’re trying to achieve is a balance between feeling hungry for air, but not panicking so as not to interrupt the continuity of exercise. The feeling we have while exercising constantly brings our attention to focus on the breath.

One of the determinants of performance in sports is the level of fatigue. For years, this topic has been studied by scientists who have tried to answer the question: what causes fatigue and how to deal with it? Can we influence endurance by changing temperature or taking painkillers? Dr. Samuele Marcora has conducted very interesting research showing that the limiting factor during exercise is not muscles but the mind. This hypothesis overlaps with the 1997 Central Governor Theory Model, which also argues that the brain is the main factor limiting maximum effort. According to Noakes, fatigue and pain signals are sent by the “Central Executive” to slow down the athlete. The brain is simply trying to protect the body, and the heart in particular, from being damaged by too little oxygen. As we get used to low oxygen through IHT training, we postpone the moment when the Central Executive triggers fatigue to slow down the pace.

Whether we play sports professionally or just run a bit not to miss the bus, our breath constantly regulates most of the processes in our body. Breathing techniques require commitment but can provide many benefits. However, even if we do not do any exercises, the mere awareness of breath can change a lot in our lives ?

Comments No Comments

Join the discussion…