Does Metabolism Slow As We Age?

You have probably often heard from slim people that they have a fast metabolism, while people struggling with excess body fat complain about slow metabolism. What is it really like? Are some of us doomed to have a slow metabolism or can we do something about it? On the other hand, can people with a faster metabolic rate eat everything without remorse? Today I will try to explain what all this is really about. Ready?

What is Metabolism?

Metabolism is the set of processes and mechanisms which take place in the body, all cells of the body, to obtain, use, and store energy from food. They are divided into anabolic and catabolic processes. Anabolism consists in creation processes that require energy, while catabolism is the breakdown of molecules into smaller elements to produce energy. They are both closely related and work together in a healthy organism thus maintaining balance, or homeostasis.

Metabolism

You already know what metabolism is, but in order to better understand what it means for your body weight, I will also introduce you to what metabolism is. Your metabolism is the amount of energy your body needs to function per unit of time, often expressed in days. This energy is essential for carrying out all metabolic processes and maintaining homeostasis. Metabolism consists of BMR (basal metabolic rate) and TBR (total metabolic rate).

TMR – is the amount of energy necessary to function at rest. It is the energy necessary to maintain vital functions while lying down in the so-called room temperature, after getting enough sleep and eating the last meal 10 hours in advance. As you may have guessed, this is not your natural environment. Basal metabolic rate is a component of TMR. It consists of BMR, postprandial thermogenesis (average 10%), and physical activity (average 30%).

Postprandial thermogenesis is the amount of energy your body needs to absorb, digest, and use nutrients from food. As a result of these processes, metabolic processes in the body are intensified.

It’s also worth taking a closer look at the physical activity itself. The so-called PAL – physical activity coefficient. It takes into account such factors as: additional (training) physical activity and the level of professional activity.

Physical activity level:

1,2 – 1,39 – A person at rest, no physical activity

1,4 -1,69 – A sedentary lifestyle plus walks or occasional physical exercise 1-3 times a week or no exercise – low physical activity

1,7 – 1,99 – Physical work, sedentary work and an hour of training (e.g. jogging) per day – moderate physical activity

2 – 2,4 – Very hard physical work (e.g. in the field, on a construction site – lifting, digging, etc.) or hard everyday training, approx. 2 hours – high physical activity

> 2,4 – Professional athlete, hard everyday training, e.g. cycling on a professional level during competition – very high physical activity.

Of course, each day may be different, so it’s important to take some time to think carefully and be honest about your activity throughout the week. Don’t forget about walking, playing with the kids, cleaning, cooking and other household chores, but also don’t skip evenings spent on the couch. In a broader perspective, one walk a week does not increase the rate of physical activity, although it is certainly better than no exercise at all.

What affects metabolism?

You already know that metabolism and metabolic rate are closely related in your body. You probably ask yourself how to influence the acceleration of the metabolic rate. There are a few things you can work on 🙂

-

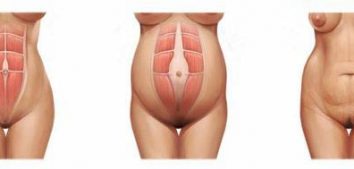

- Body composition. Muscle tissue is more metabolically active, meaning it needs much more energy to function than fatty tissue. For example, when we compare 2 people with the same body weight, but with different proportions of muscle mass and fat tissue, the person who is more muscular will use more energy – their TMR will be higher. What does this mean in practice? A person with more muscle mass has a higher energy requirement, which means they can eat more calories than a person weighing the same, whose body composition has less muscle tissue and more fat.

- Protein in the diet. First of all, the right amount of protein in the diet allows you to maintain muscle mass also in the process of reducing body fat. It is, of course, the building block of muscle tissue. Second, the body requires much more energy to digest protein than it does to digest fats and carbohydrates. This is known as postprandial thermogenesis – the energy expenditure associated with digestion. 25% of protein energy is used to digest protein, while 2-8% of energy is used to digest the remaining ingredients. Importantly, the body needs all nutrients in the right amounts for homeostasis and health. Excessive supply of protein with the diet is not recommended, as it may have negative consequences for your health.

- Physical activity. I think that I do not have to elaborate on this topic, you can read a lot about physical activity, its types and effects on the body, what you can do now, when the temperature outside does not encourage you to spend time actively, you can read HERE. The most important thing to remember is that the more you move during the day, the greater your energy expenditure. You can read about other reasons for regular physical activity HERE.

- Nutritious diet. What I mean here is that you should have

- A variety of products,

- Fruit and vegetables with every meal,

- Having whole grain products such as buckwheat, whole grain rye bread, oatmeal etc..

- Choosing lean meat and fish, including oily fish as valuable sources of omega-3 fatty acids,

- Products rich in B vitamins, which are necessary for the proper metabolism of proteins, fats and carbohydrates in the body,

- Foods rich in iodine, selenium, zinc and iron to support the work of the thyroid gland. Disorders of its operation slow down or accelerate metabolism, which disturbs the organism’s homeostasis and results in disease.

Metabolism Slows With Age – Truth or Myth?

The latest scientific reports indicate that it is not exactly the way we thought. The reason for additional, often extra pounds is reduced physical activity, not a slowed down metabolic rate!

The study was conducted by a team of researchers from Duke University conducted on a group of over 6,000 people from different countries, ranging in age from infancy to over 90 years. They studied total metabolic rate, which is a pioneering study in this topic. The results show that infancy is characterized by the greatest metabolism, after which it slows down by about 3% per year until the age of 20. Between the ages of 20 and 50-60, it stops and remains relatively constant. After reaching the age of 60, it slowly begins to slow down, but it is only 0.7% per year. Only people aged 95 and over have a 25% decrease in metabolic rate compared to people aged 20-50.

Knowing what metabolism and metabolic rate are and what affects them, you know that it is not the slowing metabolism that is responsible for the accumulation of adipose tissue. Think about what your lifestyle was like at the age of 5, 10, 15 or 20 and what does it look like now, or what it may look like in 10 years? Have you noticed that it has changed from active to more sedentary? You go to work by car or by bus, at work you spend 8 hours at your desk, in the evening you are tired and instead of walking you choose to rest on the couch. Why is there an increase in excess weight and obesity among children today? Do they also spend more time sitting? Your fate is in your hands! Take care of your health and body through a healthy lifestyle, including regular physical activity in your daily schedule.

Bibliography:

- Gawęcki J., Hryniewiecki L. (red.), Żywienie człowieka. Podstawy nauki o żywieniu, wyd. PWN, Warszawa, 2000

- Gołębiowska-Gągała B., Szewczyk L. Wpływ hormonów tarczycy na regulację przemiany białkowo-aminokwasowej. Endokrynologia Pediatryczna, Tom 4 | Rok 2005 | Nr 4(13)

- Pietruszka B., Roszkowska H., Roszkowski, Ocena niedoszacowania wartości energetycznej racji pokarmowej. w Zastosowanie epidemiologii w badaniach żywieniowych. W. Przewodnik do ćwiczeń, SGGW, 2003

- Pontzer H., Yamada Y., Sagayama H., Ainslie P., Andersen L., Anderson L., Arab L., Baddou I., Bedu-Addo K., Blaak E. i wsp., Daily energy expenditure through the human life course, „Science”, 2021, 373, 6556, 808-812

Comments No Comments

Join the discussion…